I’m just going to say it, I really like the way I look in a corset.

A confluence of things six months ago first lead me to the strange thought that I could sew a corset. The thought that I could sew one lead me straight to the idea that I should.

I’m not alone in such notions — there’s been such an explosive interest in the integration of historical clothing into modern wardrobes that it has its name, ‘history bounding.’ There’s also no shortage of YouTube tutorials for corsetry that covers everything from sewing techniques to an in-depth analysis of how each corset style affects the body’s shape.

There’s also a fair amount of misinformation about corsetry, and learning how to spot the myths made the project exceptionally enticing.

Interestingly, our society tends to acknowledge the quackery rampant in the time while simultaneously upholding some of the ‘science’ around corsetry that was produced.

In the most simple terms, a corset is a structured support garment that molds the torso into a particular shape.

Corsets evolved from stays, the structured support garment that molded the torso into a conical shape in the 1700s. Corsets continued to adapt, change, disappear, and reappear (as fashion is wont to do).

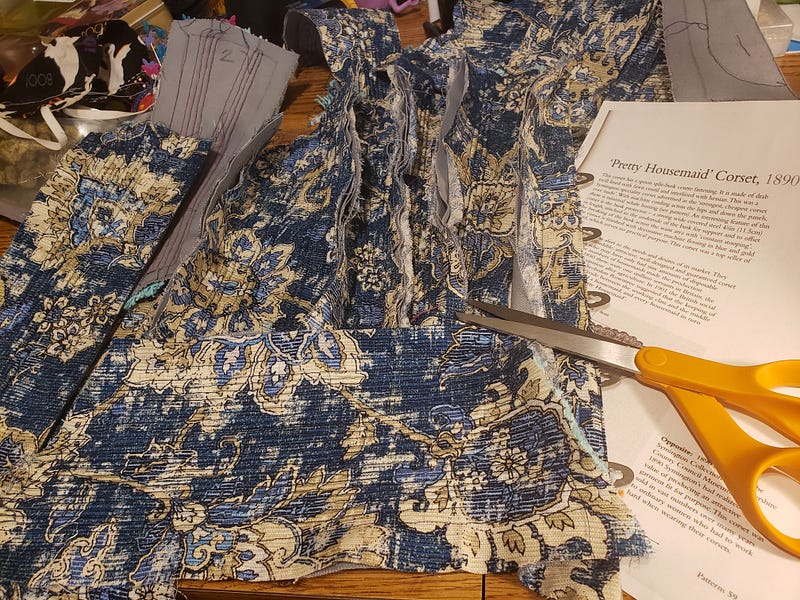

As part of my project to recreate a working woman’s corset from the 1890s, I’ve sewn my corset and have been wearing it for around 14 hours a day for the last two months.

I’ve learned a lot through the process!

Victorians were highly aware of the newest materials and methods. Corsetry showed that.

Corsets (and stays, their predecessors) manage the task of body molding by having a series of bones of rigid material. Some corsets feature only cording to perform this task, which is where strong cords are sewn between layers of cloth to create that rigid structure. I’m sure you can imagine that the more work has to be done to make the body conform to the ‘fashionable shape,’ the more work has to be performed by those bones (and their placement).

Whale gums. Not kidding.

Traditionally the bones in stays and corsets were most often made from baleen, the part of a whale’s gums that acts as a feeding filter.

That’s what’s being referred to in corset-making where it’s called ‘whalebone,’ even though it’s not a bone.

By the late 1800s, thankfully, the use of steel boning was becoming more common because, essentially, baleen was getting too expensive. The working women’s corset I modeled mine after, is named the “Pretty Housemaid” (it was marketed to housemaids) and documented and patterned in Jill Salen’s Corsets: Historical Patterns and Techniques. This particular design had minimal boning, instead depending on the cording for shaping.

While baleen has a lot of properties to keep in mind when selecting modern boning for a replica corset, there are many options to choose from that have different uses for boning in corsetry. Flat steel bones next to the lacing prevent puckering of the fabric when pulled tight.

Also, feathers. Quills, actually.

Victorians also used ‘featherbone,’ which is boning made from the quills of feathers. For modern corsetry, Spiral steel bones allow scant flexibility in one direction. Rigilene generously allows for movement but doesn’t have a lot of long-term durability. For those looking to do as true to history recreations as they can, there’s a plastic-based synthetic whalebone. For those with a time or budget crunch, zip ties can also be used!

After reading about how the Victorians approached their lives, I felt free to adapt and use the material that best suited my needs, which is very Victorian indeed.

Textiles involve a lot of work, thus textile history involves a lot of suffering.

Even beyond using whale gums to make clothing and hunting birds to extinction to make hats, the history of textiles and clothes involves suffering. Reading about it can be difficult because the thought that someone, somewhere was suffering to make all of that grand, cloth-hungry clothing happen is never far from my mind.

From the horrors of the colonialist practices of England to, well, actual slavery —it should go without saying that the history of textiles is dripping with blood.

There are a lot of conversations happening in the historical costuming community about that history, how to appropriately deal with that history, and how to ensure we learn from it.

I have been a geek about creating and using cloth for decades, and I can tell you that even the smallest square of cloth takes intense labor that many people reading this are sheltered from considering.

There’s an incredible amount of labor represented in just creating the fiber that’s used to create cloth.

Milling and spinning that fiber into a usable yarn represents more. It takes only one time warping a loom to understand how physically demanding that part of textile work is. To keep these things clean and in use and in rotation for a household was even more incredibly labor-intensive and used materials we don’t even want to contemplate (lye and urine spring to mind).

Doing any kind of study into textile arts or historical dress will intersect with the enormous human toll these tasks took. Invariably, those tolls were paid by those with little to no power.

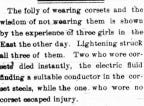

The Victorians loved a good corset horror story.

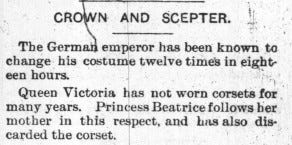

The Victorians in general were wild for any weird story they could get. The freakier and stranger the better, and it was no different for corsets. One paper clipping from the Chico Record in 1897 documents how lightning struck three girls, and the only survivor was the one not wearing a corset (the steel bones of the corset directed the ‘electric fluid.’ If it could be sensationalized and sell newspapers, then that’s what got printed.

The Victorians loved to document, which makes it a great period to make garments from.

If you want to get into historical sewing, the Victorian period is a great period, because the Victorians loved to document their lives and practices. There’s also some amazing work at restoring, recording, and patterning extant garments.

My favorite way to learn how to make the garments is mainly from their sewing manuals and correspondence courses. Manual of needlework and cutting out : specially adapted for teachers of sewing, students, and pupil-teachers by Agnes Walker, The Keystone Jacket and Dress Cutter by Charles Hecklinger, Household Sewing with Home Dressmaking by Bertha Banner (1898), and A Manual of Exercises in Home Sewing by Margaret Blair (1863) are some of my favorites. You can find a lot of these little gems on archive.org (and you’ll also find them repackaged and re-sold on Amazon, if you want copies in print).

While these sources aren’t as helpful for corsets as the Symington Corset Pattern archive hosted at Image Leicester along with amazing step-by-step instructions (or even Aranea’s Black exceptional free patterns), they are all a wonderful look into what the Victorian woman had on her mind (and in her sewing pile) at the time. You’ll also find that Victorian women’s clothes had plenty of pockets (yet another great reason for history bounding).

It was the Victorian’s love of fastidious documentation that has made it a wonderful period of fashion to recreate and be inspired by.

No matter what you’ve seen, they didn’t wear corsets next to their skin.

If you’re interested in making a corset, the first thing you should make for yourself is a chemise. Not only is it great practice, but it’s also a necessity. No matter what you’ve seen on TV or in the movies, corsets weren’t worn next to the skin — that was the job of the chemise (which helped to keep the corset clean, too!). This is especially true if the intent is to tight lace.

I thought that making the chemise was just a chore I was going to have to do before I got to make the corset — and instead I have been enjoying several different patterns and types of chemises and integrating them into my wardrobe, too! This necessary layer not only protects my skin from being pulled and pinched by the corset, but it keeps me from getting it too dirty.

Chemises, after all, are far easier to wash than corsets.

Men wore corsets, too.

It’s well-documented. The slim-waist was in, all around.

Victorians loved showing off what their machines could do.

While I appreciate those who hand-sew all of their garments as part of historical recreations, I know that Victorians would love using a machine to do the work. It was a real theme for them.

The sort of cording found in the corset that I decided to recreate is extensive and serves as a way to show off the capability of the machine and its operator in addition to giving structure and shape. There are two main ways I know of to make corded cloth. In one, you can either sew thin channels and then use a bodkin or other long, slender needle to pull the cord through the channel. The other involves carefully placing the cord against the last seam and then sewing right up against it to create the channel. Either way, having these extensive corded panels was a good way to show off all the abilities of one of the newest inventions: the sewing machine.

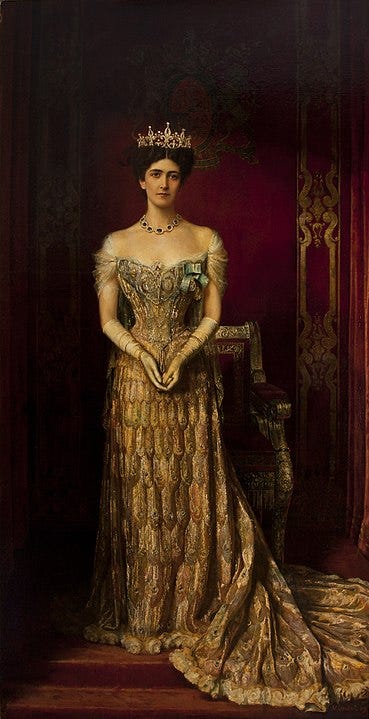

The tiny Victorian waist was partially an optical illusion.

A perfect cylinder, somewhat like what a corset creates, will appear to be smaller than the more elliptical human-torso form. Even when I only lace down to match my uncorseted measurements, I appear like I have a much smaller waist.

Victorians knew the power of good angles and optical illusions and took as much advantage of that as we do. Why else do you think they had dresses that featured enormous sleeves and the bustled bottom?

“But what about their tiny clothes, we’ve measured them?” you might ask.

The other important factor to consider here is survivability bias — the teeny-tiny clothes survived because no one wore them.

Not every Victorian woman tight-laced her corset, or even wore one.

There was an improvement between stays and corsets that allowed for more reduction of the waist, and that was the metal grommet. Before the adoption of metal grommets, lacing was done through hand-sewn eyelets which didn’t have the same durability against tight lacing (though certainly many did perform some moderate waist reduction with their stays). It was all of their technology that allowed Victorian ladies to tight-lace down to impossibly small sizes. (Don’t forget, however, that Victorians also knew how to perform trick photography.)

Just like with high fashion today, not everyone attends to all fashion trends. Queen Victoria herself stopped following fashion and stopped wearing corsets (and this was noted in papers). In 1881 the ‘Rational Dress Society’ was formed in London, encouraging a movement away from tight-laced corsets and widening skirt hoops. Women interested in rational dress would sometimes wear skirts over a pair of pantaloons named “Bloomers” for Amelia Bloomer, the temperance activist that fiercely advocated for their use in her temperance magazine ‘The Lily.’ Clearly, not every woman tight-laced her corset: the main use for such an undergarment was to support a fashionable silhouette.

The Victorians understood more about textiles than we do.

For the most part, people spent more time with their textiles before the invention of the washing machine and consumable fast fashion. Because of the labor intense processes and expense of the cloth, the Victorians valued and treasured their textiles far more than we do. Overall they embraced sustainable practices such as mending and clothing transformation far more than we do (they also helped bring consumerism to the forefront so I don’t want to overly lionize them or anything here).

There is an amazing understanding that happens when you start to create something, and I’ve learned so much about cloth from the processes of creating it from the fiber up —lessons that were baked into the day-to-day life of the Victorians. If I have hand-knit a pair of socks, there’s a way for me to mend and darn them, and I’m far more likely to because it takes a long time to hand-knit socks.

The cloth-savviness of the Victorians didn’t stop at how they cared for it.

The Victorians used layering and the properties of different fiber content to their advantage. They ensure that linen, the cloth that was most likely to stand up to the brutalities of repeated washing, was worn next to the skin, leaving the fine silks and wools free of the body’s filth. They understood how friction between layers would create heat, and that layers created from bast fibers of plants would wick sweat from the body.

While the Victorians had some pretty horrific societal values and a remedial understanding of germs and disease — they knew an awful lot about their cloth.

There are some real surprises in corset construction.

The flossing has a purpose.

When the corset is corded, it starts to have a shape all of its own.

The moments you put the bones in, it’s like the corset comes to life.

Sewing the busk taught me a level of anxiety I didn’t think possible in a hobby.

Seam construction is crazy: sew wrong sides together and welt the seams with bias tape wasn’t what I was expecting.

There were a lot of things that surprised me about the way the corset was constructed, and in some of my mockups, I intentionally did things wrong to see how they contributed to the garment’s longevity and wearability.

Victorian sewing manuals allowed for many different body types.

Many of the sewing manuals will walk the reader through sewing adjustments for the stooping form, the ‘stout’ form, the ‘erect’ form — in other words, they acknowledged that people came in all sorts of shapes, and helped sewists adjust for those shapes. There was an ideal form. Corsetry and appropriate patterning help one achieve that form.

The corset was integral for many to be able to achieve that ideal shape.

Split-crotch drawers made a lot of sense after I wore a corset.

So does the saying, ‘shoes before corset.’

I just have to come out and say it — modern underwear doesn’t play super great with Victorian corsets, it’s hard to tuck the underwear up under the bottom edge of the corset when you’re all finished. So the very first time I had to struggle to get my elastic-waisted underwear under my corset, those split-crotch drawers suddenly made a lot of sense to me.

Fashion / Dress History is still a young field and establishing itself but has so much to offer due to its experiential nature.

Once the topic is given any consideration it’s clear that not only is fashion a form of art, it also has a lot to say about history.

Perhaps it was misogyny that kept academics from taking a more serious look at the field, or perhaps it’s just easy to forget how important a tool clothing is.

Regardless of the reason it was ignored for so long, there’s a huge interest in fashion history that is growing steam.

Dress history and textile history will become more important as humankind seeks out more sustainable practices.

My corset is comforting to me.

I’m just going to say it, I really like the way I look in a corset. It also encourages me to have good posture throughout the day. The process of drafting and scaling a pattern showed me a lot of things about myself. Being able to wear the corset and use it as a tool has helped me understand a lot about sewing and a lot about the Victorian mindset. Wearing it gives me confidence not just in how I look, but in my capabilities.

What they say is true — to make a corset, all you need to do is sew a straight line.

And make a lot of mockups.

After a corset, making a lobster tail bustle isn’t hard.

Article Sources:

Pretty Housemaid Corset, 1890

Woman’s Pretty Housemaid corset made by the Symington company. A best seller of its time, made of twill lined with…imageleicestershire.org.uk

Which boning should I use for corset making?

Metal corsetry boning was invented in the 1800’s by the Victorians when their preferred corset boning of choice…www.sewcurvy.com

Women in Trousers – From Bloomers to Rational Dress

Escaping ‘the kingdom of fancy, fashion and foolery’ “The 1848 Women’s Rights Convention was the first of its kind to…helenrappaport.com

Victorian dress reform – Wikipedia

Victorian dress reform was an objective of the Victorian dress reform movement (also known as the rational dress…en.wikipedia.org

By Jamie Toth, The Somewhat Cyclops on .